There’s roughly 60 million Polish people living on the planet, and we come in all shapes and sizes. You could say there are different “levels” of being Polish. Here are those levels the way I see them.

There’s roughly 60 million Polish people living on the planet, and we come in all shapes and sizes. You could say there are different “levels” of being Polish. Here are those levels the way I see them.

Level 1: The Prodigal Pole

In the Bible, there’s the story about the Prodigal son, who ran away from home and wasted his wealth and talent on meaningless pleasures before finally hitting rock bottom.

Prodigal Poles are those people of Polish descent who have “run away” from their nationality. They have no interest in learning about their Polish ancestors, language or culture. Some of them might even know Polish and have gone to Polish school, but refuse to ever speak it out of shame. If given the choice between a vacation in Poland or getting wasted with strangers in Indiana, they would probably choose the latter. The only hope is that, like the prodigal son in the Bible, the prodigal Pole will see the light and come back…

Level 2: The Developing Pole

Out of all five levels of being Polish, the developing Poles deserve the most respect. They may be several generations removed from a Polish ancestor but are nevertheless heavily invested in discovering their Polish past. From researching genealogy, to trying out Babcia’s recipes, to reading Crazy Polish Guy, these Poles desire to know everything they can about Poland.

Although many of them don’t speak a word of Polish and have never visited Poland, they are, perhaps, the purest Poles due to their genuine desire to learn about their nationality. Their motivation comes from the heart, and that’s what matters most.

Level 3: The Proud Pole

Proud Poles are typically those who grew up in a strong Polish household or have developed in their knowledge of Polish culture to the point of showcasing it whenever possible. They speak Polish when they can, listen to Polish music, attend Polish events, go to Polish Mass and generally make Poland a regular part of their lives.

Proud Poles typically celebrate all major Polish traditions with their families—from Wigilia to Fat Thursday. They treat their colds with AMOL, gorge on Kołaczkis and have probably seen the movie Sami Swoi at least twice. Through their undying love for Poland, proud Poles ensure that the old ways will carry on.

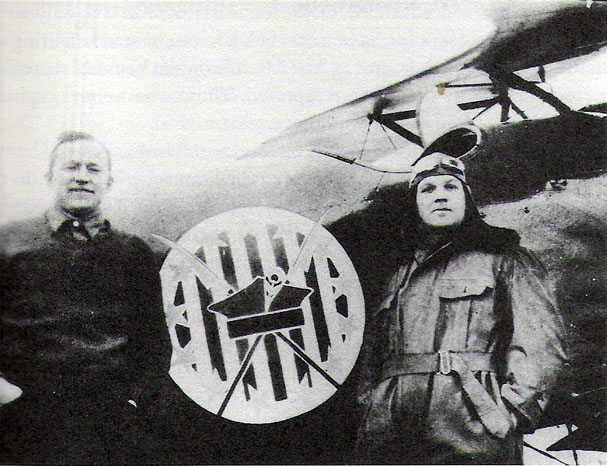

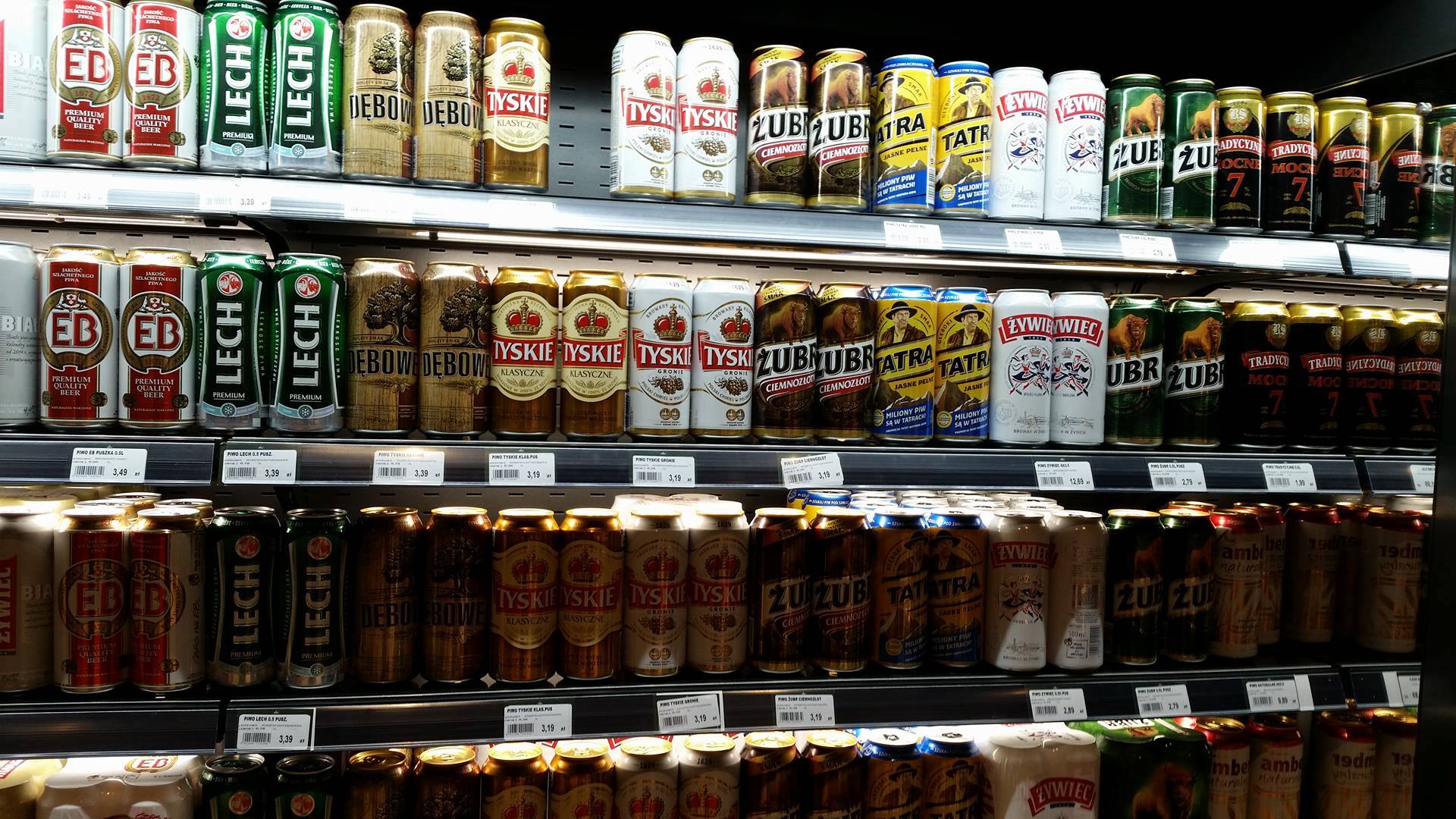

Level 4: The Crazy Pole

Level 4: The Crazy Pole

Consumed by the Polish spirit, the crazy Pole cannot go a day without doing or saying something Polish-related. He’s a nutcase who annoys his friends by bringing Polish beer to EVERY SINGLE get-together and will ramble for hours about how the Poles saved Europe in 1683.

The crazy Pole is not satisfied to live out his Polish culture and let others be (unlike the proud Pole). He actively promotes it, disseminating information about Poland whenever possible so that others too may understand the glory of that blessed nation. He takes developing Poles under his wing and does what he can to bring prodigal Poles back into the fold. A word of caution before becoming a crazy Pole: you run the risk of people viewing you as Polish and little else. If you’re ok with that, then jump on in. The water’s fine.

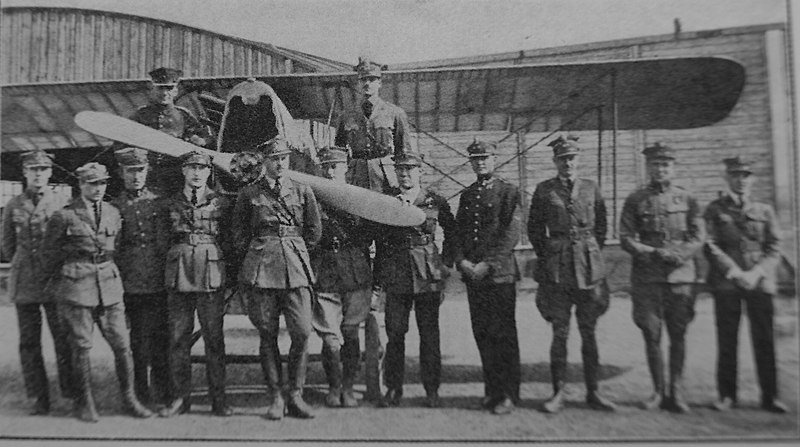

Level 5: The Actual Pole

The highest level of being Polish…is actually BEING Polish. You were born in Poland and Polish is your native tongue. You don’t have to do any of the other stuff because you can just say “I was born in Poland.”

Of course, just because you were born in Poland, doesn’t mean you can’t be horrible at being Polish. Although you cannot change your blood and birthplace, you can choose to ignore it. It’s possible for an actual Pole to also be a prodigal Pole if he or she has chosen to forget where they came from—that’s probably level zero of being Polish.

I guess the highest level, then, would be a crazy Pole who was actually born in Poland. But is the world ready for that?

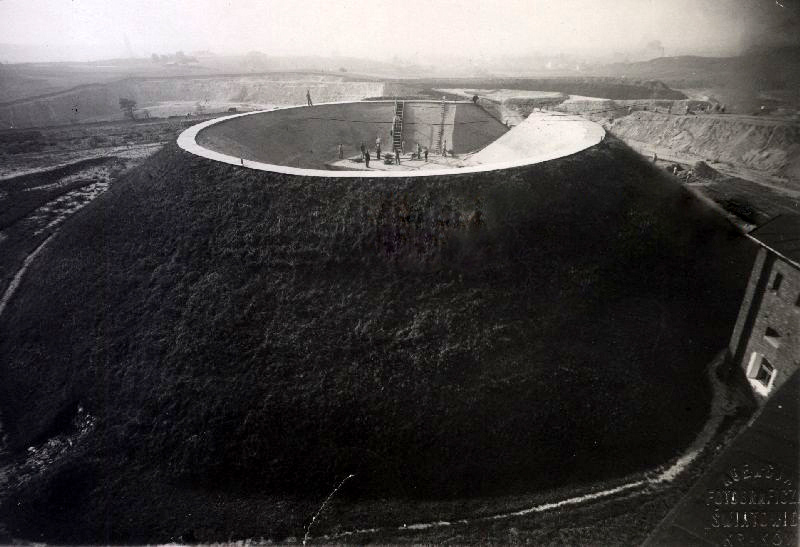

On the southern bank of the Vistula River in Krakow lies one of the city’s most ancient mysteries. Anyone could mistake it for a large hill, but it’s not—at least not a naturally-made one.

On the southern bank of the Vistula River in Krakow lies one of the city’s most ancient mysteries. Anyone could mistake it for a large hill, but it’s not—at least not a naturally-made one.

Christmas Eve in Poland, known as Wigilia, has some very beautiful traditions. Breaking the Opłatek wafer, caroling, opening gifts, the midnight mass, or Pasterka–these are practices beloved by every Pole and person of Polish descent, including myself.

Christmas Eve in Poland, known as Wigilia, has some very beautiful traditions. Breaking the Opłatek wafer, caroling, opening gifts, the midnight mass, or Pasterka–these are practices beloved by every Pole and person of Polish descent, including myself.